If you have worked on any software project solo or with a team, you have made code commits. You might do it dozens of times a day without much thought. But a commit is more than “saving your work.” It is a core building block of how modern software is developed, reviewed, debugged, and shipped.

This article will examine Git code commits and the importance of understanding and implementing good commit practices, especially in engineering team environments.

What Is a Code Commit?

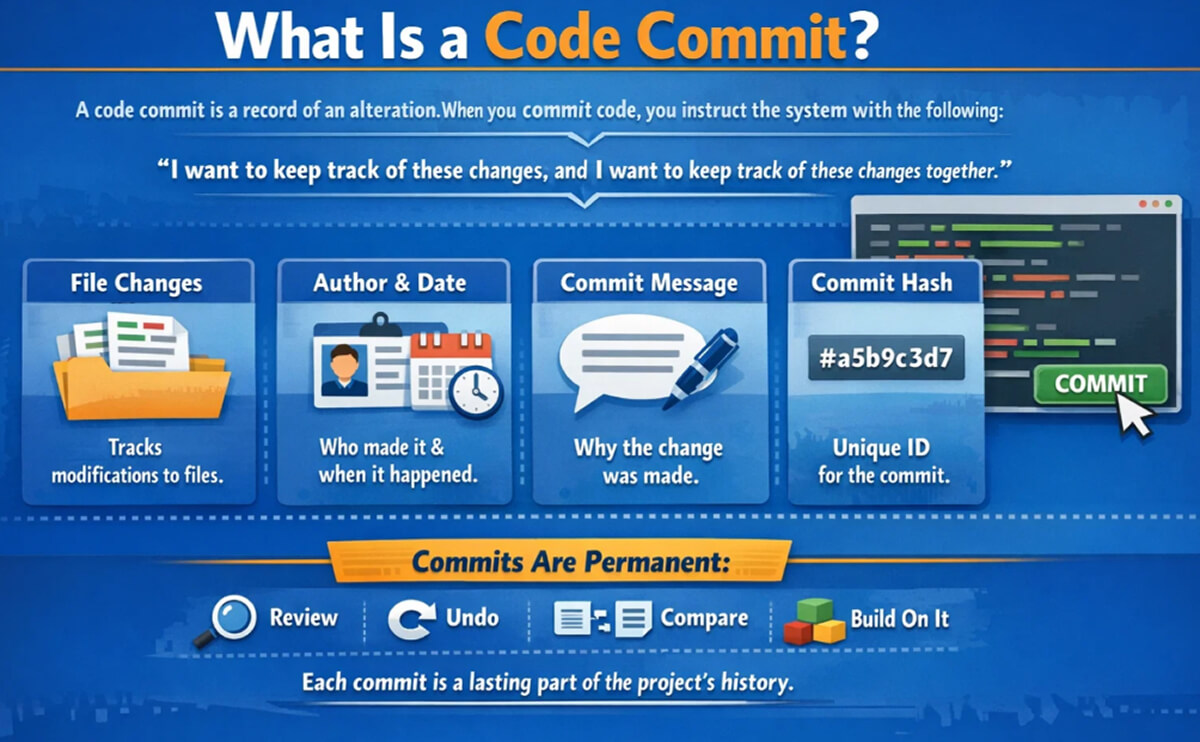

A code commit is a version control system’s record of an alteration. When you commit code, you instruct the system with the following:

“I want to keep track of these changes, and I want to keep track of these changes together.”

In Git, a code commit tracks the following:

- All the changes made to one or multiple files.

- Information about the author and when the commit was created.

- A commit message that explains why a change was made.

- A unique identification code, referred to as a commit hash.

Once you create a commit, it is permanently part of the project’s history. You will be able to look it over, undo it, compare it to others, or build on it over time.

Why Code Commits Matter More Than You Think

At first glance, commits seem simple. But in practice, they power almost everything around modern development workflows.

Well-structured commits help teams:

- Understand why changes were made.

- Track down bugs more quickly.

- Review pull requests efficiently.

- Roll back risky changes safely.

- Automate builds, tests, and deployments.

Poor commits do the opposite. They create confusion, slow reviews, and make debugging painful.

Git and the Commit Model

Git is a distributed version control system. That means every developer has a full copy of the project history. Commits are the currency that keeps everything in sync.

Each Git commit:

- Points to its parent commit or commits.

- Represents the repository’s consistent state.

- Is effectively permanent once created, because you usually create new commits instead of editing old ones.

If you want to go deeper into how Git stores commits and objects, the official Git documentation is a solid reference.

The Git Commit Command (Basics)

The most common way to create a commit is using the git commit command.

A typical flow looks like this:

git status

git add .

git commit -m "Fix null pointer error in user profile"What is happening here:

- git status shows what has changed.

- git add stages the changes you want to include.

- git commit records those staged changes as a commit.

Writing Good Commit Messages

Commit messages are not comments. They are documentation.

A good commit message answers one key question: What problem does this change solve?

A simple structure that works

Short summary (ideally under 72 characters)

Optional body explaining why, not how

Example:

Fix race condition in payment confirmation flow

Requests could complete out of order when retries

were triggered under high latency.

What to avoid

- “Fixed stuff”

- “Update”

- “Changes”

- Long, unstructured paragraphs

Atomic Commits: One Idea per Commit

An atomic commit describes one logical change.

That means:

- One bug fix

- One feature

- One refactor

Not all at once.

Why this matters:

- Easier code reviews

- Cleaner rollbacks

- Clearer history

If your commit message requires the word “and” multiple times, it is probably doing too much.

Commit Frequency: How Often Should You Commit?

Although there isn’t a universal rule, it is helpful to commit your changes when they are complete, correct, and testable.

That may mean:

- Every 10 to 20 minutes for small fixes.

- A few times per day for focused feature work.

While frequency is essential, what is more important is the intent behind the commit. Each one should signify a notable milestone.

Commits in Team Workflows

In team environments, commits do not live in isolation. They flow through systems.

Typically:

- Commits are pushed to a remote repository.

- Pull requests are created.

- CI pipelines run tests on each commit.

- Reviewers inspect commit history, not just final diffs.

In this case, the smoother and cleaner the commits are, the less friction there is in the review process. If the commits are messy, they will slow everything down.

Rewriting Commits (When It Is Okay)

When working with Git, there are some ways to modify the commit history using:

- git commit –amend

- git rebase -i

This is useful when:

- Cleaning up local commits before a pull request.

- Fixing commit messages.

- Squashing noisy changes.

Important rule: Never rewrite commits that someone else has already pulled. Once a commit is pushed, consider it permanent.

Common Commit Mistakes Developers Make

Even the most seasoned developers have to deal with:

- Committing classified information and generated files.

- Combining behavior modifications with refactors.

- Committing messages that are not descriptive.

- Making large ‘catch-all’ commits.

- Using commits as checkpoints instead of backups.

A good way to avoid this is to wait a moment before clicking the commit button and ask, “Would it make sense to revert this change?” If the answer is no, try breaking the commit into smaller ones. Before staging, also use git diff to confirm that you are not committing any logs, build outputs, or local configurations.

Code Commits as Communication

At the most basic level, commits are a way to communicate.

If you are communicating with Git, you are also communicating with co-workers, reviewers, on-call engineers, and your future self. If you have a clean commit history, production incidents are easier to analyze because you can look back and see when a behavior changed and which commit introduced it.

A good commit will indicate what changed and why. A great commit will also indicate intent. If the commit is meant to lower the cost per query, prevent duplicate requests, or make error handling explicit, then that gives the reviewers the context to trust the change.

Final Thoughts

Making code commits is straightforward, but being good at it takes effort. It is not useful to rely on your tools to help facilitate good coding commits. It is better to rely on your discipline instead.

Keeping your commits small and documenting the project’s history will help you code faster and improve your collaboration with others.